Chapter 16. Saying Good-bye

"I am going, 0 Nokomis, On a long and distant journey, But these guests I leave behind me, In your watch and ward I leave them; See that never harm comes near them, See that never fear molests them, Never danger nor suspicion, Never want of food or shelter, In the lodge of Hiawatha!" | ||

| --Hiawatha | ||

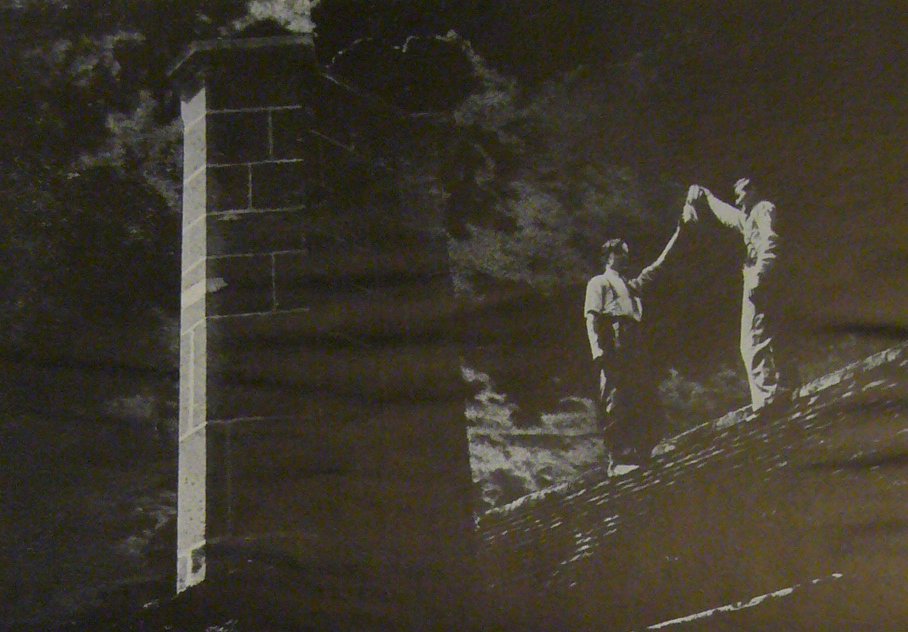

All that now remains is to take our leave, as gracefully as may be, and melt away into the darkness we have loved. The narrow line which separates the sublime from the ludicrous runs through time as well as space, and we have reached that line. No longer may we test ourselves up pipe and chimney; the days of early manhood become as out of date as those of the nursery, and we must say farewell.

There is a French saying that the first love is the only true one. Probably this is more true of places than of people. Somewhere in the heart of every one of us there is a place he loves more than anywhere else, It may be his old school, or the place where he was born; his present home, or somewhere where he spent a holiday with particularly vivid associations. He might be able to give no valid reason for his preference but it is there, and time, which dims other memories, keeps these fresh. Across the choppy tide of time certain landmarks stand out, motionless and fixed in the receding waters. Some of them we can talk about, some we keep very secret, but we all have them. They are the unseen milestones of our journey, anseen often to ourselves until a certain light reveals them for a few moments, like the sun casting a silhouette of distant islands. Or perhaps there is but one, marking a corner which none but ourselves know me have turned.

Whatever it is, we each have something like this on which to look back. And thinking about it, we realize that love is infectious, and spreads of its own accord. We may love a place where we loved a person, or a person whom we met in a place we loved. Things interconnect strangely with unfore- seen results coming from simple events, and from a simple love, if it be intense enough, the focus may blur and the light in- crease, until we find ourselves possessed of an overwhelming love of everything around us.

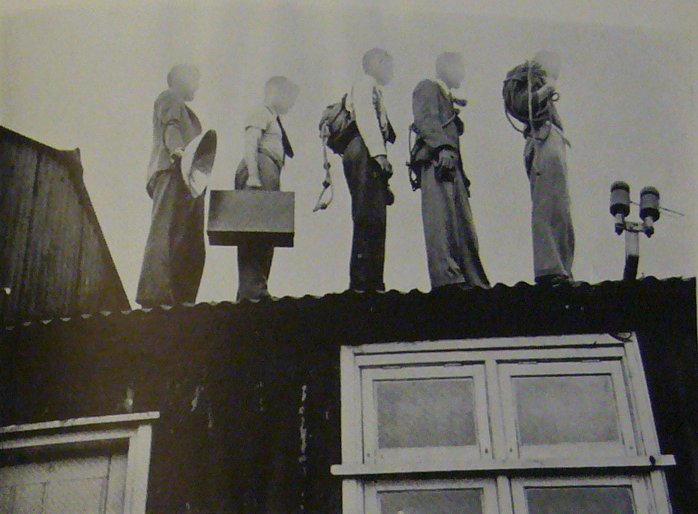

We ourselves have loved Cambridge. Many hundreds of young men must go through the same experience every year, for the undergraduate is at an emotionally susceptible age. To each it comes in its own way, each accepts it according to his character. Memories of Cambridge may conjure up old friends, weeks and months of hard work followed by successful exams, thrills on the football field, morning coffee in the cafés, convivial evenings of beer-drinking, hilarious twenty-first birthday parties. But not to us. Cambridge brings back a jumble of pipes and chimneys and pinnacles, leading up from security to adventure. We think of those nights spent with one or more friends, nights when we merged with the shadows and could see the world with eyes that were not our own.

Now it is all over, and as the evening draws on we sit in an armchair by the fireside, comfortable with slippers and a book. When the hour comes that we should go out, in a polo sweater and black gym shoes, we yawn and think of bed. We resist the temptation to steal another hour from the night, to read another chapter. There are new worlds to conquer, and we must be ready.

The future is waiting, in its smile a tremendous invitation, and we must try to win favours from it. It will not tolerate half-heartedness, and as it absorbs our energies we think less and less of those great moments of the past. Already, we seldom live through them again. Yet since this is a farewell, and we are stepping out of yesterday into to-morrow, we will lay down the book and answer questions we have never before asked ourselves.

First, why did we start night climbing? Was it an irrepressible gambling instinct, with ourselves the dice, and the pleasure of teasing destiny as our winnings? Was it an attempt to emulate men we knew to be better than ourselves, and by doing what they did to imagine ourselves their equals? Was it the hypnotism of an immense terror drawing us in in spite of ourselves? Was it sheer animal spirits finding an outlet? Certainly not the latter. All the former reasons may have played their part, for human motives are more complex than the strangest chemical compound. The primary cause was probably an urgent need for self-discipline, though this quickly gave way to enjoyment of the thrills that came. Chance also played its part.

One autumn day some years ago we were slowly walking through Cambridge, in despair at our utter inefficiency. There was no taste in anything. Nothing was so easy but was too difficult, the lightest task was too much effort. We had just missed a supervision because it had seemed too much trouble to walk across the court. Life had sunk to a stage of sitting vacantly and waiting for the next meal. A complete and permanent tack of interest had set in. Something drastic was needed.

Summoning the last vestiges of mental energy, we vowed to do the hardest thing we could think of. lnstead of failing, through lack of interest, in the multitude of things that had grown so tiresome, we would come back to life, not quietly, but with a gigantic achievement as a kick-off. It was the only hope. With something like this behind us, the effort of living would become easier, and the successful effort would embody itself in our character. But what was there that we could possibly find to serve the purpose? It was the darkest hour.

At this moment we looked up and saw the spires of King's Chapel. Here was the answer. Though we had known the fascination, we had always felt a strong fear of heights. We had no qualification, mental or physical, for the job, except a

strong desire not to jellify into permanent unconsciousness. If we could do it, we should recover. Thus we started night climbing.

Many climbers probably start somewhat in the same way. It is one of the simplest ways in which a man can come to grips with the deficiencies of his character. He may be full of fears; in climbing he can conquer them and see himself doing it.

From the height he reaches, his range of vision increases, and he sees himself as well as the world around him. Imagination is brought into play. A mere cog, he finds himself in sympathy with the machine. Climbing can bring only good to those who indulge in it; it is a stimulus from which there is no reaction.

If we are so often frightened while climbing, why do we enjoy it? This is a harder question to answer. It is partly the sense of achievement, partly the thrill of taking apparently big risks when subconsciously we know the danger to be very small. "If this or that should happen," a climber is continually telling himself, "I shall go spinning." Yet he knows it will not happen. A hand-hold may occasionally break off, but never the vital one he is forced to trust. The sense of danger is much greater than the danger itself.

It is probably the sense of danger which is the basis of the stimulus which comes from climbing. Fear, in its cruder forms, is protective. The nearness of the danger increases the sensibility of the mind, puts keenness onto the mental edge. A climber is enlivened by an appeal to the same instincts which came into the daily life of his ancestors. Nothing is so precious as when we seem to have run a risk of losing it.

For a climber is as a man standing on the edge of an abyss. The chance of falling over or of the ground crumbling beneath his feet is negligible, yet his very closeness to the edge makes him think. He cannot but visualize what would happen if he stepped forward, and realizes with a shock of what very small significance it would be. The sun would still be shining, and the waterfall would still be roaring below. And suddenly he realizes, perhaps far the first ttme in his life, what a friendly fellow the sun is, what vividness there is in the green around him.

There is a kind of fear which is very closely akin to love, and this is the fear which the climber enjoys. It is, to use a contradictory term, a brave fear; a fear which announces its presence, perhaps very loudly, but raises no insuperable barrier to achievement. The climber enjoys being frightened, because he knows that fear is no impediment.

Lastly, we may ask ourselves whether the good effects resulting from climbing are permanent. From the pinnacle of our premature old age, we think we can say they are.

The immediate exaltation after a difficult climb only lasts two or three days at the outside, but there is a residual effect after the effervescence has died down. The imagination, through its violent and constant use in climbing, receives a permanent increase in strength. It becomes constructive instead of haphazard, so that instead of thinking what he might do a climber thinks more of what he could and may do. Each achievement makes the next one easier.

And so, sitting in our armchair by the fireside, we smile as our thoughts carry us back to Cambridge. It has been great fun. These last few weeks have been equal to the best of the old days in college, when to go out involved so little effort that we did so all too rarely. The trouble with the camera, the climbing, the excitement after each flash, the long car journey of over fifty miles up to Cambridge in the evening, night after night, and the return in the darkness before dawn, the hedgerows rushing past on the edge of vision, the feeling of control as the tyres gripped on each corner taken too fast, the moon shining her torch on a sleeping world, or the sense of the country around on a dark night; the memory of bad climbers forcing themselves to be brave on easy buildings, and good climbers arousing our admiration on the severe climbs; the feeling of knowing intimately all those with whom we have been out. Yes, it has been great fun.

Occasionally, as we pause in our reading to throw a log on the fire, we feel a vague unrest. It all seems too comfortable. The night is dark, and in its inscrutability tries to lead us on to action; or the moon laughs down, as though trying to tell us what she can see in other parts of the world. We stir in our chair, and wonder whether it is a sign of strength or weakness that makes us ignore the call. Cambridge is there, just over an hour from us, her roof-tops waiting.

While we pause, the wind rattles the casement more fiercely than ever, and seems to mock our hesitation. "You who sit there, action is life, and by your fireside you are ceasing to live. Shake the mothballs from the old polo sweater you have always worn, and come out again. The night and I have always been your friends, do not desert us now. We will tell you secrets, as we used to tell you secrets in the past, and old friends will unite again." Thus he tempts us, and when we refuse he changes his tone, and accuses us of cowardice and lack of initiative. He raises uneasy phantoms, which claim to be our former selves and point accusing fingers at us as usurpers depriving a better self of its home.

Bringing all his guile into play, he begins to produce the desired effect. Doubts begin to assail us, tremendous fears of we know not what, and looking at the fender, our eyes grow large and round. Then someone enters the room, and we are our old laughing selves again. No one ever knows our deepest thoughts.

So we step out of one era into the next, and as we close the book it must remain closed for thirty years, until that time when the past begins to look longer than the future. There are others to follow; at this very moment there may be a dozen climbers on the buildings of Cambridge. They do not know each other; they are unlikely to meet. In twos and threes they are out in search of adventure, and in search of themselves. And inadvertently they will find what we found, a love for the buildings and the climbs upon them, a love for the night and the thrill of darkness. A love for the piece of paper in the street, eddying upwards over the roof of a building, bearing with it the tale of wood-cutters in a Canadian lumber-camp, sunshine and rivers; a love which becomes all-embracing, greater than words can express or reason understand.